(Editor’s note: An ONS news team accompanied an elite squad of Sellwood Rangers and their legendary leader as they patrolled the Oaks Bottom Bluff, the volatile border region contested by wildlife forces, vehicles and people. This report contains a graphic image, and was subject to review by regional security officials.)

ALONG THE BLUFF BORDER — Among themselves, quietly, the other Sellwood Rangers call her “Blind Sunny.” Always spoken with a glance her way, a head bob and a tail quiver of respect. She’s 12 and white eyed, but the wire haired commander is still boss of the block and boss of the bluff.

If Blind Sunny hears them, which she probably does, she doesn’t let on. A leader doesn’t always have to say anything, and Sunny keeps her own counsel, most of the time.

She leads by example, as leaders do. She still volunteers for all-day porch duty, and gives first alert when the mail carrier approaches or delivery vans idle up the block. She’s first at the fence, too, when other dogs need to be told to move along. Her partner, Toby, yaps, sprints and bounces like a madman when other dogs come by, but he’s just a sideshow and everybody knows it.

The other Rangers laugh and say that Toby’s nickname at the humane society was Napoleon, and how it totally fit him. He’d be a crazy little dictator if Sunny let him, but she doesn’t.

He’s a sight, the other Rangers say, but they smile when they say it, because Tobias is such a character. He’s little — part beagle, part chihuahua, probably some pug. Wild teeth splayed out of an underbite. He’s desperate about food, and he’ll eat anything, even cat turds if he can get them. He was picked up as a skin and bones stray on the streets around L.A. somewhere, so maybe that made him crazy about food.

The story is that the Portland people who brought him home didn’t want to keep that Napoleon name. What would you call him for short, they argued. Nap? Pole? Then the man remembered the Sherlock Holmes stories, and how Sherlock sometimes borrowed the services of a Scotland Yard tracking hound named Toby. So Toby he became.

He’s the squad’s designated lunger, so he’s always leashed up. But he is a natural rear guard, gifted at it. On patrol he’ll frequently stop, turn and look behind, and if he sees something, he turns to stone until the man stops and looks, too.

The Rangers say it’s a wonder Blind Sunny didn’t take one look and shake him by his neck folds when the people took her out to meet him at the humane society. The man had predicted she wouldn’t like him, that he was too bossy, but she liked him from the start. All of a sudden she had somebody to chase in the yard, and they still play-fight nearly every day. They’ve been partners for seven years; Toby is about 9 now but acts 90 sometimes, the people say. Sunny’s at least 12.

She came from the humane society, too, in 2013. She was also from the LA area and the people at the humane society thought she was about 3, then. Her person down there had given her up, apparently, and it was obvious her pups had just been weaned away; her teats were still slightly swollen.

The people say there’s always been a sense of melancholy about Sunny, even though she’s always been playful, alert and terrier tough.

Toby remains good company for Sunny, who still grieves her kids, and whose eyes turned white.

And the other Rangers call her Blind Sunny now, because she is nearly so. Other people notice and say oh, is she blind, and Sunny’s man says yeah, but she’s got the Poop Patrol path memorized and gets along fine. Sometimes she taps the air a couple times to find the curb and step up, but mostly she gets along fine. The other Rangers see her jaunty trot and are reassured.

The man tells other people she’s just a sweetheart. She likes people, she greets everyone, and she is particularly patient and calm with children. The man calls her Sunny Sun, quite often.

But the Rangers say Sunny’s all business out on Poop Patrol. She’s still out front, nose down and tail up as she trots confidently on the sidewalks and on the patrol path, the grass and mud trail that runs parallel to the street and looks down on Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge. The man does some of her looking for her; he’ll tell her to wait if he thinks she may not know something’s there, like a car coming or a step down, or a branch in the way. Wait, Sunny, and she listens.

The man unhooks Blind Sunny when the squad loops down 9th or 7th and back on the sidewalk along Malden Street. That’s how much he trusts her. Sometimes Sunny visits with Colby, who is the dog she likes more than any other. The man says he’s never seen her react that way with any other dog, dancing to play with him. Unbelievable.

Toby just lunges at Colby, so the man shortens up his leash and holds him back. The man says Toby is an asshole, sometimes. And insecure. But loyal as hell; he follows the man everywhere.

The newest Ranger is Gus, the young cat scout who volunteered for patrol duty one morning and kept doing it. He’s not even 2 and walks the path his own way. Blind Sunny ruffs at him sometimes, especially when he streaks past her nose on purpose. But she recognizes the tactical advantage of having a squad member willing to jump down the bluff into the tall grass or vault up a tree for a look-around.

Having Gus out on the perimeter and Toby on rear guard allows Sunny to sniff the path and figure out who’s been along it. Other dogs, of course, most of them familiar and routinely remarked upon. Sunny was spayed at the humane society and hikes her leg to pee almost every time. Then she’ll huff and scratch up the grass and dirt to make her presence and her point clear to other dogs.

But other dogs are a routine presence on the bluff border. The real threat comes from the wild creatures who creep in from the edges to trespass and steal. Disgusting rats and ridiculous squirrels chief among them, of course. The other Rangers say Sunny hates vermin, and if she catches them in the yard or in the house, they’re dead. She’s caught a couple of foolish squirrels on the ground outside, and that was the end of them. Another time the man found a dead momma possum in the back bushes and two of her kids stretched out dead on the patio. That was Sunny’s doing, no doubt. She just hates vermin. Over the years she’s finished off several rats the cats had brought into the house alive and let go.

Not that she needed to polish her reputation, but Sunny’s relentless attacks singlehandedly won The Battle of Skunk Shed a couple years ago. The Rangers call it singlepawed, by the way.

A skunk momma and five bumbling babies moved in under the shed. Over the course of a week or so, Sunny drove them out, killing one and nearly getting another. She got sprayed three times, the Rangers say.

Toby got sprayed once and from then on stayed 10 meters back, barking and hopping. He says he was backing Sunny up and keeping them away from the house. The other Rangers laugh, even Blind Sunny.

Worse and much more dangerous are the raucous, vicious raccoons that hunt for garbage and climb the cedar trees next door to scream and fight amongst themselves.

Gus made a name for himself earlier this year with his scouting work on a raccoon patrol that approached the people houses.

The vile raccoon, testing windows, didn’t know he was being watched himself. Gus doesn’t miss a thing, and that’s why Sunny let him come along on Poop Patrol. Blind Sunny thinks Gus is undisciplined, sometimes, but she knows talent when she sees it.

Besides that he’s cautious about cars, which is crucial. He’s stealthy and streaky quick, too, and has the athletic ability to get away from coyotes if he ever has to. He can be up a tree or even a utility pole in seconds flat. He vaults up trees just to show off, sometimes, and leaps to swipe at crows midair if they dare swoop him.

The oldest Ranger is Rosie, the famous assassin. She’s 14, thin, and getting crazy. She doesn’t go more than a block on patrol anymore, and yowls when the others continue on to the bluff. Mainly she does yard and porch duty these days, and the other Rangers say she’s still a fearsome presence.

She used to scout like young Gus does now. Over the years she brought dozens of rats, mice and birds back to the people house. The man sometimes found quivering birds atop the curtain rods or cabinets, and was able to catch them in a kitchen towel and take them back outside to recover. Many actually flew off. Rosie was quick and stealthy enough to catch hummingbirds, the other Rangers marvel. Unbelievable, they say.

Rosie went her own way, too. Sometimes the people wouldn’t see her for a couple days. One of the people neighbors said Rosie used to come into their house and hang out, which was OK with Rosie’s people, because the other people obviously treated her well or she wouldn’t have gone over there.

Sunny huffs at Rosie sometimes, just for fun to make her yell and run away. When Toby showed up a couple years after Sunny, however, Rosie decided she wouldn’t take getting pushed around by two dogs. Once Toby tried to jump onto the couch, not knowing Rosie was there, and she clubbed him on the top of his head. No claws, just a melon thump you could hear from the kitchen. They get along fine now, probably because Toby never tries to boss Rosie.

The people say Toby is friend to cats, and he is that. He and Gus hang out quite a bit, when Gus bothers to come inside.

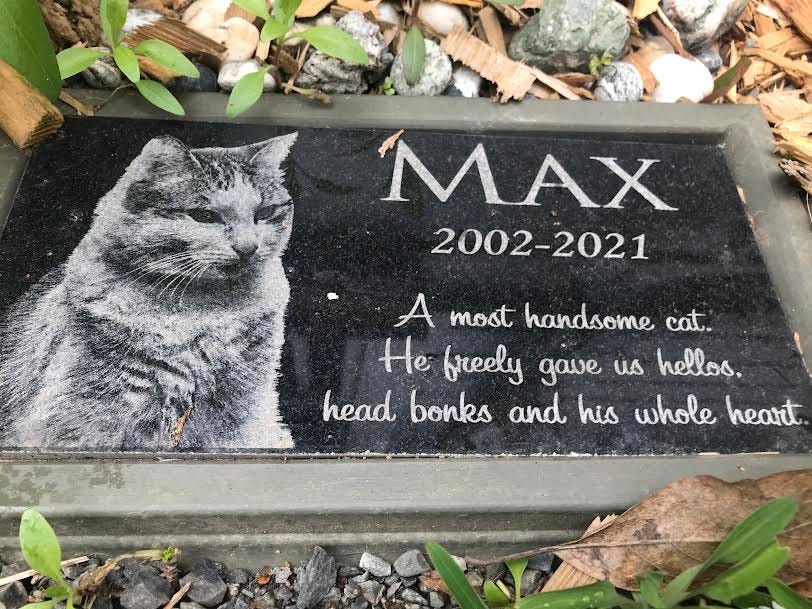

Rosie was the second pet in the people house, after the beloved Max. After Max died, Rosie went into a tailspin and yowled and quit eating, quit drinking and nearly died herself. The people got Gus, the young scout, because they thought Rosie needed company.

Of course, she pretended she didn’t like him, and hissed at him when he approached. But over the past year she’s eaten better, gained some weight, hisses less and seems more active. The people think she appreciates having another cat around, but still won’t cuddle with him yet.

The funniest thing between the two of them happened when Gus was still a kitten and Rosie was still acting like she hated his guts. She brought in a mouse, dead, and paraded past him to get his attention. Then she tossed it in the air and batted it around. When she went past him again, she dropped the mouse at his feet.

The people say she was telling him, “Do it like that.” She never had any kittens of her own, but somehow that momma instinct kicked in.

Gus isn’t Max, though, and Rosie loved Max. Everybody did.

Max wasn’t a Ranger, but everyone agrees he set the bar for behavior. He was magnificent, a gem of a cat. Head bonk and chin rub friendly, smart and a constant talker. And he never ran from dogs.

The Rangers say there are tons of tales to tell about Max. How he brought that baby possum into the house and set him down under the table during the Hanukkah dinner that one year. Brought it in and set it down like it was his kitten, or maybe his contribution to the meal. The people scrambled up and said what the hell. And the baby possum backed up between Max’s paws, seeking protection.

They tell how Max used to groom Rosie, licking her head as they lay together in front of the fire.

Max used to wake the man early each morning. Gently, slowly sticking one claw on the man’s cheek to make him get up and provide some breakfast.

Max answered every time the people spoke to him. Such a talker, so much to say.

Max lived to be 19. At the end, cancer was rapidly eating away his left ear and sometimes he toppled when he tried to stand up. The man took him to the vet to have him put down and held him close as they did it.

One of the assistants, a kindly, tattooed, ring-pierced man, put Max on the scales to weigh him, so he could measure out how much sleepy death dope the vet should administer.

When the assistant leaned in to check the weight, Max gave him a head bonk.

That was Max.

He’s buried on the side of the people house, next to the Old Rose that was transplanted there.

Those are the kind of stories the Sellwood Rangers tell when they’re back from poop patrol and have had their breakfast. When the people house is secure, the bluff border is safe, and they warm themselves by the fire. Then Toby hits the couch, Gus jumps back out the cat door, Rosie finds a pillow and Sunny steps out for porch duty.

Tomorrow morning the Rangers will do it again. Assemble at the entry when Blind Sunny barks to the man, and head out.

Just thank you for growing up to be so swell.

In Hood River, other packs head out to keep the world safe as well. Their lost members are mourned tenderly as are these brave and worthy souls. I always enjoy reading your blog.

I would like to educate you and your readers about opossums; they are not vermin. They look weird. Anyone with over 50 teeth probably would. They do eat just about everything but are not vicious and don’t generally go after pets, as they’re often accused of. They’re actually pretty shy. And their two best tricks are eating ticks by the zillions and being impervious to rattlesnake venom. They’re the source of anti-venom. So there’s my little public service announcement for opossums. Thanks!